27 January 2021

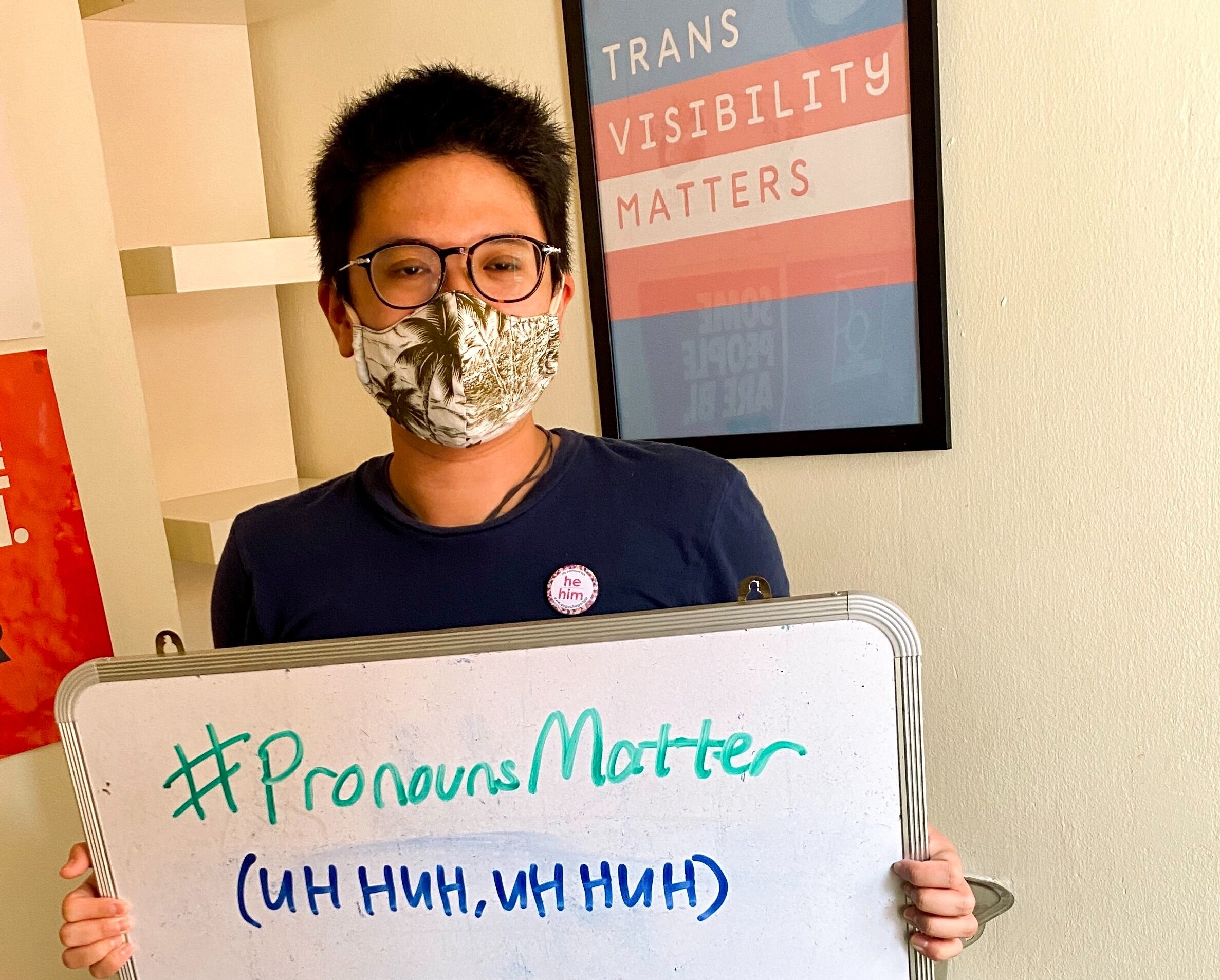

The following is a guest contribution to the newsletter “We, The Citizens”, written by Alexander Teh. Alexander (he/him/his) is a youth worker with Oogachaga.

In 2018, then-Minister for Education Ong Ye Kung said that there’s no discrimination against the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) community “at work, housing (and) education” in Singapore.

The sheer confidence with which he made his proclamation made me want to believe him, despite knowing full well that this wasn’t, and still isn’t, the case.

In a recent Reddit post, 18-year-old transgender student Ashlee (not her real name) shared being denied the right to proceed with hormone replacement therapy while continuing her education in junior college. This happened despite her producing a psychiatrist’s letter confirming her diagnosis of gender dysphoria — a prerequisite for transgender people in Singapore to commence gender-affirming medical treatment.

[Note: Hormone replacement therapy, or HRT, is one of the treatments recommended for individuals who are diagnosed with gender dysphoria — the psychological discomfort experienced by a person whose gender identity does not match their assigned sex at birth.]

Although Ashlee’s parents have consented and are supportive of her transition, the school insisted that she’d have to keep her hair short, in accordance with the school’s rules for boys. She was also told that she had to keep wearing the boys’ uniform, and to ensure that her hormone replacement therapy wouldn’t result in physical changes that would prevent her from fitting into it.

Not complying with these conditions would mean expulsion from school.

While the Ministry of Education (MOE) has disputed this account, Ashlee’s case isn’t an isolated one. As a gay transgender man, I’ve personally experienced and heard of other instances of discrimination towards LGBTQ+ students in the formal education system.

Unlike Ashlee, I never went to junior college. My secondary school years were extremely unpleasant (and I also failed Combined Science), so that’s when I decided the polytechnic route was for me, and my time in a school uniform ended. But during that time, I, like Ashlee, had to contend with rigid school rules, ill-informed teachers and school staff, and downright uncomfortable everyday school experiences.

My classmates and I were made to sign abstinence cards after a very passionately delivered sexuality education class. At the tender age of 13, we vowed not to have sex until we were in a “faithful”, monogamous marriage with someone of the opposite sex. We were only taught about boy/girl relationships. A good friend of mine who was seen holding hands with her younger sister on school grounds was pulled aside by a teacher, and told in hushed tones that “this is not the correct way to behave”. We would overhear teachers and staff mocking their colleagues and gossiping about students and who they thought was a “butch”, or “fairy”, or “pondan”, or “bapok”, or “tranny”.

I was made fun of for my rapidly developing body, a body I tried so desperately to hide under an oversized school blouse and a slouch that I’m still trying to get rid of years later. After I confided in one of my favourite teachers about how I felt, she brushed it aside, telling me to get my hormone levels checked and “sorted out” and I’d be all right.

There are no known policies that protect LGBTQ+ students against discrimination on the basis of their sexual orientation and gender identity, nor is there a curriculum that teaches children about, and affirms, diverse identities. Adolescence is in itself a trying time for many; for young LGBTQ+ people, especially those who are transgender, feeling the need to hide their journey of self-discovery and identity, so as to avoid being bullied, is exhausting and demoralising.

What upsets me the most hearing about Ashlee’s case is being reminded, yet again, that Singapore hasn’t only failed in tackling discrimination against a marginalised community; we’ve also denied a young person their right to education in a safe, affirming environment.

Ashlee has other options to continue her post-secondary education; she’s said that she’s considering leaving junior college and going to a polytechnic instead. But this isn’t a choice that she should have to make; she has every right to pursue her chosen path. Nobody should have to choose between their education and their freedom to be their authentic selves without fear.

Unfortunately, even after hanging up our school uniforms for good, there are other hoops for us to jump through. Transgender folks experience various instances of discrimination well beyond our school years. The absence of legal protection means that transphobic employers can reject our applications or fire us for being transgender. Lengthy government job application forms require male applicants to declare their National Service — an experience that transgender women often find awkward and unpleasant to share, and one that transgender men do not have.

Marriage — and by extension applying for public housing and adopting children — is often off the cards for many of us who aren’t in straight relationships, or those of us who haven’t changed our sex markers on our NRICs. That is, if we’re lucky enough to be able to change our sex markers at all: ICA now requires transgender people to undergo invasive genital reconstruction surgeries, and be examined by a specialist before being allowed to make the change on our documents. Even though gender affirming surgeries have been proven to have long-term benefits on transgender individuals’ mental health, it isn’t covered by insurance companies in Singapore, rendering a happy, healthy life inaccessible to many, particularly younger transgender people.

I turn 26 this year. It’ll be ten years since I’ve left the formal education system. It frustrates me greatly knowing that, although my country places great emphasis on the quality of formal education, it ignores young LGBTQ+ students fighting to live their lives authentically in their schools — places that young people should be able to consider safe harbour. Do we really believe in ensuring each child has the opportunity to an education when we insist on policing who they are allowed to be as individuals?

This is a reminder of the desperate need for MOE, and the rest of the government, to re-evaluate their priorities. Perhaps then, future Ministers for Education can stand in Parliament and declare that there is no discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community at work, housing, and education… and actually mean it.